HPSG

From a syntactic point of view, the smallest constituents (= pieces) of sentences are words. So, it is natural that our syntactic journey begins with words. If you think about it, you need to know a lot about a word in order to use it grammatically:

- its pronunciation

- its part of speech

- its valence, i.e. the number and type of subjects and objects it combines with

- its meaning

- and perhaps its inflection (things like case, tense, and agreement).

If a formal, i.e. precise grammar is supposed to model what speakers who use the grammar know about their language, then the grammar will have to precisely represent all the information in the list above as well. So, let us look at how Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar represents lexical information (= information about words). We will see that similar words have very similar lexical entries.

Words

Let us look at a fairly simple class of words, namely names:

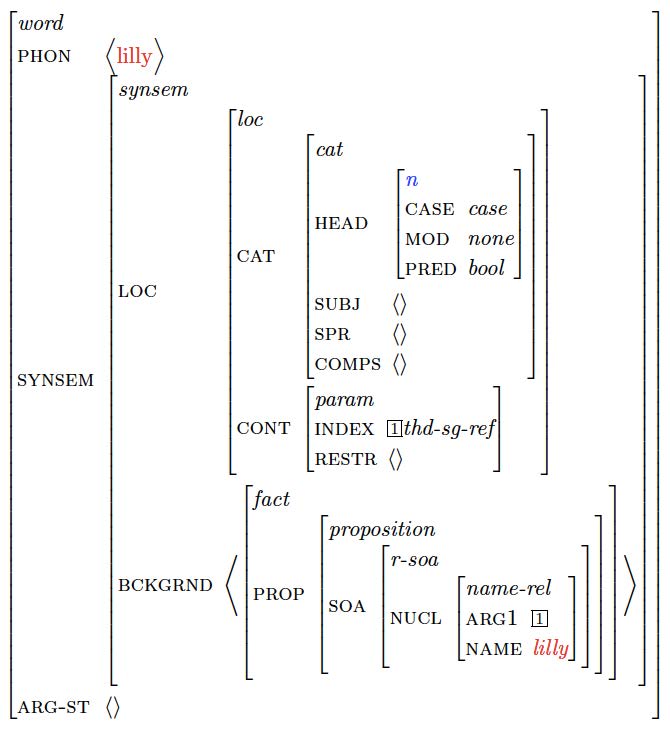

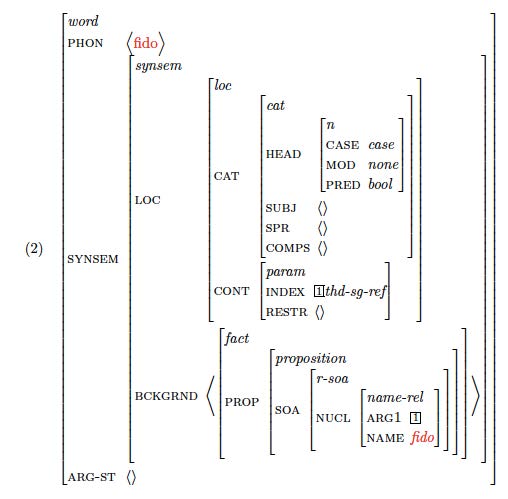

We put two words next to each other, the word Lilly on the left and the word Fido on the right:

That looks like a lot of information, but recall that in the previous section we recognized that speakers know much about the words of their language!

So, let us go through the list we made earlier and see where and how each type of information is contained in the structures above. Since both words are names, we would expect the two representations to have something in common; but since they are different names, we would also expect them not to be completely identical.

In the top left of both representations, the word word captures the fact that Lilly and Fido are both words, rather than phrases or sentences. Let's now go through the list of word properties that we collected above

We begin with the first item on the list: speakers know the pronunciation of the words of their language. Is this information contained in the two representations above and if so, where? You will probably have spotted the attribute PHON in both words. On the left it takes the value <Lilly>, whereas on the right it takes the value <Fido>. This is how we represent that the words Lilly and Fido have the pronunciations that they do. At this point, you should protest and say that in-between the angled brackets we have just written the letters that make up the spelling of these words rather than the phonological segment that make up their pronunciation! Congratulations: you would be absolutely right!!! In fact, you have noticed a trick that syntacticians use all over the world when dealing with phonology. When it doesn't hurt, i.e. when we are really dealing with syntactic issues that are not influenced by the phonological properties of words, phrases, and sentences, then we simplify our lives by substituting the spelling of words for the representation of their phonological segments in terms of the International Phonetic Alphabet. If you promise to keep the secret, then you are allowed to use this trick as well, but only as long as you do syntax!

Returning to our two words above, we have already found 3 things that they have in common and one where they differ: (i) both are marked as word, (ii) both have a PHON attribute, expressing that they have a phonology, and (iii) in both cases the value of this attribute is a list of "segments", in truth letters. The difference that we found is that the PHON value is <Lilly> in one case and <Fido> in the other.

The second piece of information in our list of properties that speakers know about the words in their language is their part of speech. Traditional grammar categorizes both words as nouns. In our formal theory this is represented as the blue n at the end of the path SYNSEM|LOC|CAT|HEAD. Do not worry for now about the meanings of the elements in the path, those will be explained in due course.