Syntax 1 Wiki: Week 5

Tracking the stucture-building process in detail

This week we are going study every detail of the licensing of phrases. For this purpose, we are going to study the interaction of the following concepts:

- Word definitions

- Phrase definitions (again)

- Unification (= the merging of feature structures)

- The Head-Feature Principle

Types

A language like English has several ten thousand words in its lexicon and each word in turn contains a lot of information, among others:

- Phonological information: how the word is pronounced

- Semantic information: the word's meaning

- Morphological information: information about case, verb form, etc.

- Syntactic information: the word's part of speech and its valence.

Each word may then contain a dozen or more pieces of information. If you multiply this by the tens of thousands of words in a natural language, that makes a huge amount of information. In fact, lexical knowledge, i.e. the knowledge of information about words, by far makes up the largest part of what speakers know about their language! This means that the lexicon will be the largest component of a grammar. Therefore, it is very important that we capture this information as effectively as possible.

This is where the notion of a type comes into play. Before explaining what a type is, I give a number of examples from which you will probably already be able to guess what types are and why they are so useful. Probably all of you have a smartphone. Even though these phones may be from different manufacturers and may be different models, they are all smartphones. So, if your parents ask you what you want for your birthday and you say that you want a new smartphone, then they know that they shouldn't get you a TV set, a tennis racket, or a bicycle. All of these, smartphones, TV sets, tennis rackets, bicycles, etc. are types of things. Even though not all smartphones have the same properties and neither do all TV sets, etc. all smartphones have things in common that distinguish all of them from TV sets or tennis rackets.

The website www.dictionary.com contains the following information:

type: a number of things or persons sharing a particular characteristic, or set of characteristics, that causes them to be regarded as a group, more or less precisely defined or designated.

Why, then, are types so useful? Because they contain information about not just one thing, but potentially a (large) number of things, as the definition above says. Therefore the following procedure is effective: if many items in a grammar share a particular characteristic or set of characteristics, then we can define a type as having these shared properties. For all the elements that behave alike because they all have the properties of the type, we simply state that they are things of that type. In this way, we do not need to repeat in their definitions the same set of properties over and over again. It is in that sense that using as many types as possible makes a grammar very efficient!

Types and Subtypes

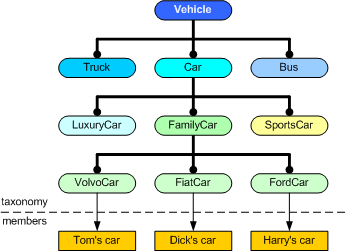

Look at the following picture. It contains a particularly clear and systematic classification of a type of objects, namely vehicles. We are going to use it to introduce some important concepts and technical terms which can also be used in organizing grammatical information.

(Source: http://www.infowebml.ws/intro/index.htm)

The picture contains of two parts, separated by the dashed line towards the bottom. Above the dashed line, we find a systematic classification of vehicles (such a classification is also called a taxonomy, but we don't use that term in linguistics). The pieces of the classification are all types. All the way at the top, we have the type Vehicle. This means that every individual object that falls under the hierarchy is a vehicle (the individual objects in this case appear at the bottom: Tom's car, Dick's car, and Harry's car). Directly below Vehicle, we find the three types Truck, Car, and Bus. These are specific types of vehicles. The type Car is further divided three times, and the middle type Family car as well. The dashed line now signals that the hierarchy of types ends here. We will come to the bottom line in a moment. Before we do that, we introduce some important technical terms and illustrate them with the picture above.

Type

Every node in the hierarchy (above the dashed line) is a type. A type stands for a class of things.

Illustration:

The types in the vehicle hierarchy are the following: Vehicle, Truck, Car, Bus, LuxuryCar, FamilyCar, SportsCar, VolvoCar, FiatCar, FordCar.

Subtype

The subtypes of a type t are all the types that can be reached from t by following branches downward in the hierarchy. The subtypes of a type stand for more specific things of that type.

Illustration:

- The subtypes of type Vehicle in the vehicle hierarchy are the following: Truck, Car, Bus, LuxuryCar, FamilyCar, SportsCar, VolvoCar, FordCar, FiatCar.

- The subtypes of type Car in the vehicle hierarchy are the following: LuxuryCar, FamilyCar, SportsCar, VolvoCar, FordCar, FiatCar.

- The subtypes of type FamilyCar in the vehicle hierarchy are the following: VolvoCar, FordCar, FiatCar.

- The types of type VolvoCar, FordCar and FiatCar have no subtypes.

Immediate Subtype

An immediate subtype of a type t is every subtype that can be reached by going just one step down in the hierarchy.

Illustration:

- The immediate subtypes of type Vehicle in the vehicle hierarchy are the following: Truck, Car, Bus.

- The immediate subtypes of type Car in the vehicle hierarchy are the following: LuxuryCar, FamilyCar, SportsCar.

- The subtypes of type FamilyCar in the vehicle hierarchy are the following: VolvoCar, FordCar, FiatCar.

- Since the types VolvoCar, FordCar and FiatCar have no subtypes at all, they also have no immediate subtypes.

Maximal and Non-maximal Type

A maximal type is a type which has no subtypes. "Maximal" here means "maximally specific." Correspondingly, the types which do have subtypes are called non-maximal.

- The maximal types in the vehicle hierarchy are the following: Truck, Bus, LuxuryCar, SportsCar, VolvoCar, FordCar, FiatCar.

- The non-maximal types in the vehicle hierarchy are the following: Vehicle, Car, FamilyCar.

The Type Hierarchy

Definition A set of types ordered into types and subtypes is called a type hierarchy.

Objects and Types

So far we have only talked about the upper part of the picture below. Now, we are going to turn our attention to the lower part and the relationship between the two parts.

(Source: http://www.infowebml.ws/intro/index.htm)

Recall that the upper part of the picture represents types ordered from most general (the type vehicle), to more specific (all the types in the second and third rows), and finally to most specific (the maximal types VolvoCar, FiatCar, and FordCar. All these types stand for classes of objects, with vehicle being the biggest class and the maximal types being the smallest.

In contrast to the types in the upper half of the picture, the three items below the dashed line do not stand for classes of objects, but to individual objects. That is why the creator of the picture labeled the lower part of the picture members.

Illustration

Tom's car is an individual object. The downward arrow from the type VolvoCar to the object Tom's car means that Tom's car is of type VolvoCar, i.e. is a member of the class of Volvo cars. But since, VolvoCar is a subtype of the types FamilyCar, Car, and Vehicle, this means that Tom's car also belongs to the types (and the classes they stand for). In other words: Tom's car is a Volvo car, a family car, a car, and also a vehicle. As a result, Tom's car not only has all the properties of a Volvo (= its maximal type), but also all the properties of a family car, a car, and a vehicle (the non-maximal types that it belongs to)!

Objects Can Contain Other Objects

Let us now look at a second picture. Click on the link below and then on the Back button of your browser to come back here.

What you see is the illustration of a car and its components. Below the picture, the parts of the car are grouped together into functional units, for instance the cooling system and the the gas supply system. These parts of the car can be viewed as objects in their own right which each belong to a type one might call car part. The type cooling system might then be an immediate subtype of the type car part and might have the types radiator and cooling fan as its own immediate subtypes.

All this illustrates that objects which themselves belong to certain types may contain other objects as their parts and those objects again belong to one or more types!

Summary

Here is a summary of the our discussion of objects and types:

- Every object belongs to one maximal type and all the supertypes of this maximal type.

- A type of object may contain objects of other types.

- An object has all the properties of every type it belongs to, both its maximal type and its non-maximal type.

- The unification of a type with one of its subtypes yields the subtype, since the subtype contains more information than the supertype and additional information.

Unification

We begin with the concept of unification. It simply means that you combine the information that you have about an object from two or more sources. Or, to put it differently, you combine two descriptions of the same object. Here is an example.

The easiest way to understand unification, is to see it in action.

Pickpocket Scenario 1

Imagine that Jill and Jack are at the Frankfurt Christmas market together. At some point, they see a pickpocket stealing somebody's purse. By the time they have alerted the police, the pickpocket has disappeared. The police officer asks them for a description of the pickpocket and gets the following answers:

Jill: the pickpocket

- is a man

- has blond hair

- was wearing a jacket

- the jacket was black

Jack: the pickpocket

- is a man

- was wearing a jeans

- was wearing a jacket

- the jacket had a zipper rather than buttons

As there was only a single pickpocket, the police officer assumes that Jill and Jack are describing the same person. She gets on her radio and tells her colleagues to look out for a person meeting the following description:

the pickpocket

- is a man

- has blond hair

- was wearing a jeans

- was wearing a jacket

- the jacket was black

- the jacket had a zipper rather than buttons

10 minutes later, a man meeting this description is arrested and the stolen purse is found on him.

Pickpocket Scenario 2

The same scenario as above, just that now Jill and Jack describe the pickpocket as follows:

Jill: the pickpocket

- is a man

- has blond hair

- was wearing a jacket

- the jacket had buttons rather than a zipper

Jack: the pickpocket

- is a man

- was wearing a jeans

- was wearing a jacket

- the jacket had a zipper rather than buttons

Again, the police officer assumes that Jill and Jack are describing the same person. The combination of the informtion in their descriptions yields the following new description:

the pickpocket

- is a man

- has blond hair

- was wearing a jeans

- was wearing a jacket

- the jacket had buttons rather than a zipper

- the jacket had a zipper rather than buttons

This combined description is inconsistent, because there is no jacket that can have both of the properties in the final lines at the same time. We say that if the unification of two or more sets of information is inconsistent, then unification fails. Or, to put it differently, when unification fails, then the two descriptions cannot be unified.

Self-test exercises on unification

File:Unification-exercises.pdf

File:Unification-exercises-solutions.pdf

Word definitions

The second ingredient we need in order to track the details of the structure-building mechanism is word definitions.

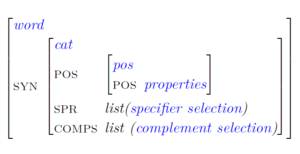

We postulate that in order to be legitimate, every word must have the following structure:

We have seen many examples of this. There is nothing new here.

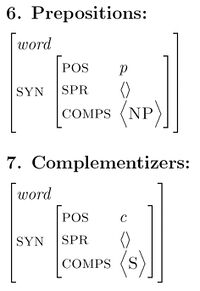

But words belonging to the same part of speech may have to meet additional constraints that distinguish them from words of other parts of speech. Here is a list of those constraints for the word of the 7 parts of speech which our grammar contains:

Individual words add properties to the schema of their word class whose combination singles out a particular word. Here are some examples. Compare the structures below to the general format of words and the schema for their word class above.

Phrase definitions (again)

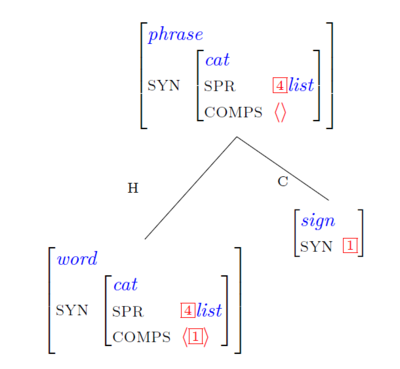

Now that we have words and know how to unify feature structures, we return to the definitions of syntactic phrases again. Last week, we already saw the definition of Head-Complement Phrases, repeated below:

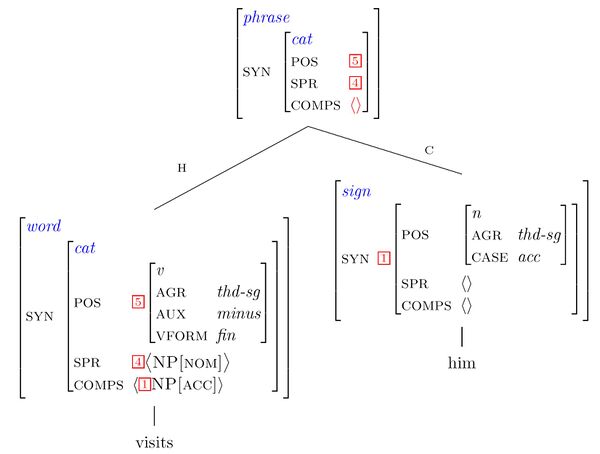

Building the head-complement phrase visits him

If our goal is to build the head-complement phrase, then we need 3 grammatical objects which we already have:

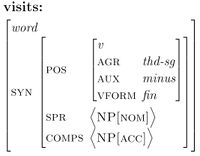

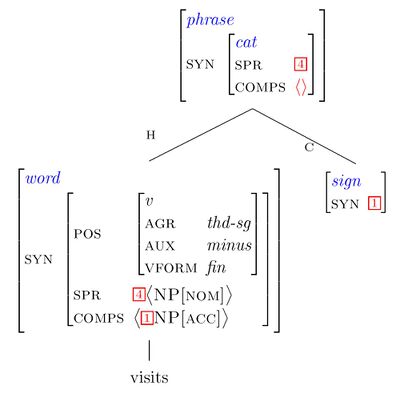

1. The word visits:

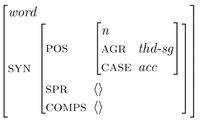

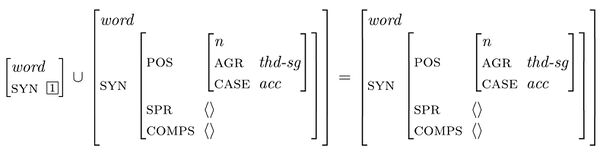

2. The word him:

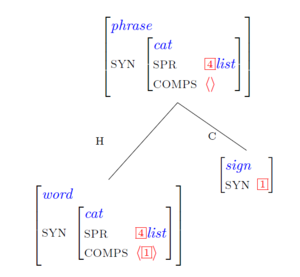

3. The schema for head-complement phrase

We proceed in two steps:

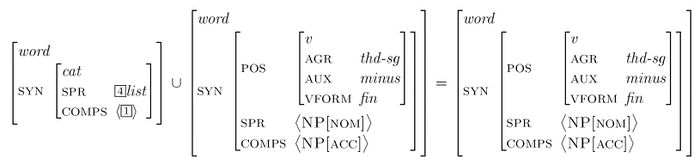

Step 1: Unify the feature structure of the word visits with the feature structure of the head daughter of the head-complement phrase:

This results in the following partially specified head-complement phrase:

Step 1: Unify the feature structure of the word him with the feature structure of the non-head daughter of the head-complement phrase:

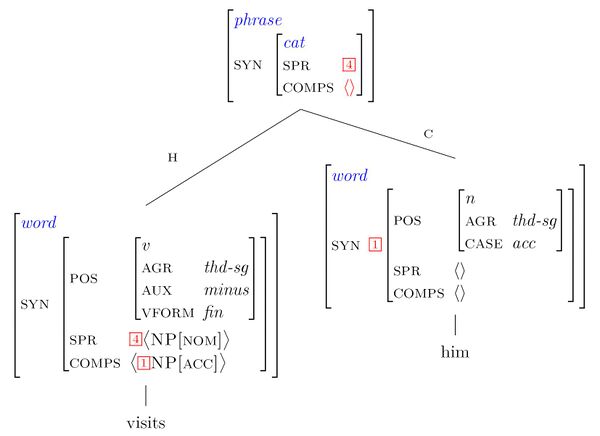

The result is the following head-complement phrase, where both daughters are now specified:

4. The Head-Feature Principle

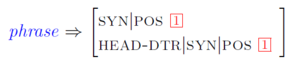

Recall the content of the Head-Feature Principle:

Since the head-complement phrase visits him is a phrase, it must satisfy the Head-Feature Principle. So, we need to unify the whole tree with the righthand-side of the principle. This result of this unification is the following tree:

Now, the head-complement phrase visits him is complete. What could you do with it at this point?

Navigation: